Victor writes about STAR WARS (sorta)

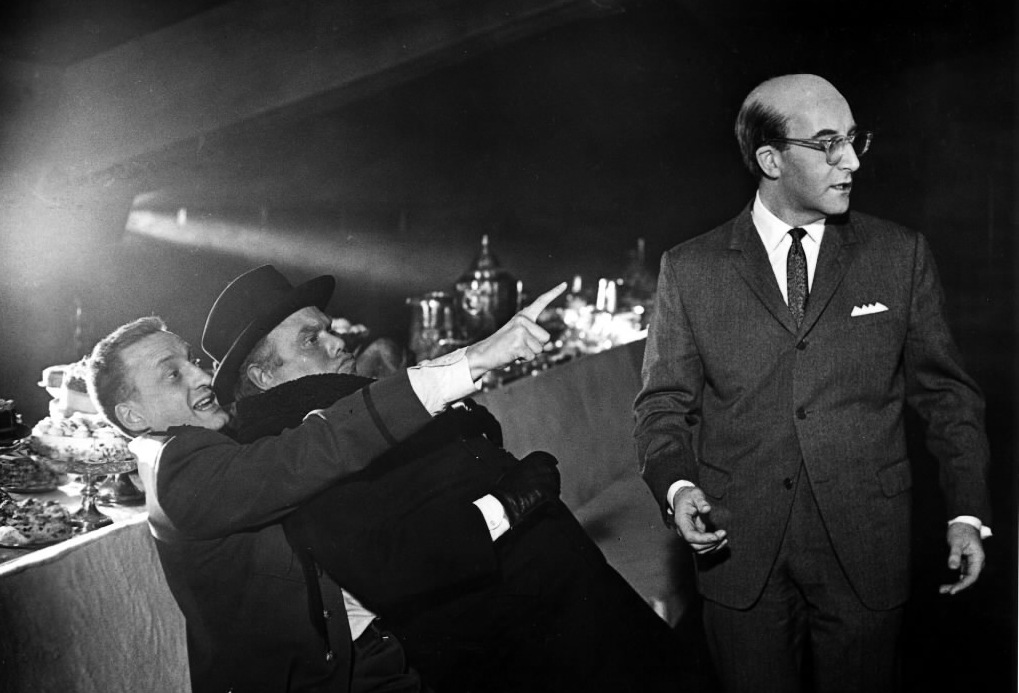

Yesterday’s kerfuffle about the director of the latest STAR WARS movie reminded me of this scene from THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS:

This clip ends before we get to the punchline of which I was reminded, when Uncle Jack returns after escorting Eugene out, and says to George:

Well, it’s a new style of courting a pretty girl, I must say, for a young fellow to go deliberately out of his way to try and make an enemy of her father by attacking his business! By Jove! That’s a new way of winning a woman.

I have no stake whatsoever in the STAR WARS INC. products, having seen only the first, second and fourth of the films. But I have some interest in the backlash afoot about the director Disney hired for the next movie in the series. While Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy’s most recent work includes episodes of MS. MARVEL and an animated series 3 BAHADUR, she won her fame (and two Oscars) as a Pakistan-based journalist making documentaries about the oppression of women and related issues in Muslim countries. A Canadian citizen with degrees from Stanford and Smith, Obaid-Chinoy will be the first woman and the first non-white to direct a STAR WARS film, a fact that naturally was the lead on all the stories and which she herself leaned into.

“We’re in 2024 now, and it’s about time that we had a woman come forward to shape a story in a galaxy far, far away.”

Kathryn Bigelow became the first woman to win the Best Director Oscar by making a war movie and she came up through action and genre films. The best action film I’ve seen in recent years was directed by South Asians (the Tamil blockbuster RRR). John Ford directed two Oscar-winning documentaries. So … there’s plenty of precedent for great action movies coming from biographies, backgrounds and resumes like Obaid-Chinoy’s. Nevertheless, “Pakistani feminist documentarian” doesn’t exactly scream “next STAR WARS movie.” I’ve been accused of hero worship regarding Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, but I’m pretty sure they couldn’t make a STAR WARS movie that the fans would want to see.

The backlash goes beyond mere identity though (if it didn’t, it would be ridiculous and unworthy of other comment). Matt Walsh posted this the other day of Obaid-Chinoy providing a kind of self-manifesto.

I like to make men uncomfortable. I enjoy making men uncomfortable […] It’s only when you’re uncomfortable and have to have difficult conversations that you will, perhaps, look at yourself in the mirror and not like the reflection.

Now this clip is several years old and isn’t specifically talking about STAR WARS or even her work on MS. MARVEL. But personnel is policy and her “about time” words from this week aren’t those of someone who’s backtracked from that way of thinking. And those older words are incredibly shocking to people who didn’t go to Smith or Stanford. And they are, at a minimum, a very bad look for the maker of a commercial film costing hundreds of millions of dollars rather than a crusading journalist (I’m sure her work in that sphere, with which I’m unfamiliar beyond titles and premises, is worthy and important).

I absolutely believe the artists should not pander to the box office. But producers, i.e., the people who hire directors, should worry about the box office. Worrying about the box office is THEIR role. The STAR WARS movies are a commercial product with a huge built-in audience, not an artisanal personal work. Hiring a Pakistani feminist documentarian who says she enjoys making men uncomfortable to direct a film with a pre-existing fan base that is largely male … well, as Uncle Jack would put it, by Jove! That’s a new way of winning an audience!

These sorts of pre-backlashes (and thus arguably baked-in failures, however unjust) happen because people inside the left-culture bubble don’t understand just how they sound to people outside it … which is pretty much what defines a bubble after all. They can’t read an outside room.

Look at that clip again and note how Obaid-Chinoy gets applause for saying she wants to make men feel uncomfortable and goes on in full pedagogic crusader mode, almost like a schoolmarmish Carrie Nation, saying half the human race needs to shut up, agree and obey. And notice how the one male on the stage takes it with meek resignation, like a well-trained housepet. This is a forum where everybody agrees and Obaid-Chinoy says what she does because (ironically) this is NOT a difficult thing to say for her, in this space. (An actually difficult conversation, for most of the people in that room, would spark cancellation calls and intersectionalist anathema sits and accusations of thisism and thatphobia.) But STAR WARS fans are not intersectional feminists. “I like to make men uncomfortable” sounds like sadistic male-hatred to people who have never gone near a women’s studies course. And outside the bubble, the conversation is over and the mind is closed (“you hate men”).

Yet the typical reaction from those who have gone near a women’s studies course and liked it (I’m not linking to the article, which is just hateful snark) is to double down as if disagreement were per se vindication. But if one’s goal is making others uncomfortable, i.e., trolling … I suppose it is.

Japan World War II Apologist, redux

As I’ve already written here, I very much liked the new Godzilla movie, and so did the two people with whom I saw it, both Godzilla junkies. Since then I’ve had four independent conversations with non-critic friends about GODZILLA MINUS ONE, all initiated on the specifics by them, the most recent being Monday, and all of them liked it on more or less exactly the terms I describe in my review. And we know the film is generally popular, managing the amazing feat for a live-action subtitled film of being #1 at the box office the week it opened.

In that review, I noted that I jokingly call myself in my Twitter bio a “Japan WW2 apologist.” It’s an in-joke with a friend who called me that (sarcastically himself), because I could not bring myself to care that Miyazaki’s THE WIND RAISES is about a man who designs a fighter plane as a thing of beauty but leaves out all Japan’s WW2 atrocities (a point of criticism at the time, especially among the wokest Americans).

But in Monday’s GODZILLA MINUS ONE conversation with a co-worker, he told me about a dissent that he had read, in National Review. It’s bizarre, he told me. I said “by Armond White then?” (that meant nothing to him). After having now read it, I don’t know if the more bizarre thing is the review itself or the fact it wasn’t by White (I’m unfamiliar with author Michael Washburn).

Washburn does make one good critical point, that it shares a lot of similarities with JAWS, and he adds that here they get a plethora of bigger boats. But something tells me that his concern is more with something else.

My concern is more with the identity of the good guys in this action-adventure. Godzilla Minus One is set in 1946, and the heroes are Japanese soldiers and sailors who vocally resent their defeat in the war and its lasting consequences for Japan’s empire. …

From the opening, when the kamikaze pilot who could not bring himself to do his duty to the empire in the past watches the tragic deaths of his fellow soldiers at the hands of the monster, through the scenes in which Godzilla ravages the mainland, and defeat has deprived the nation of the means to fight back, to the later scenes when an officer who acts as if the war is still going on gives a rousing speech to members of the demobilized fleet, Godzilla Minus One is in the Japanese military’s corner. You might view the monster as the specter of Japan’s wartime enemies, haunting the psyche of a people, crying out for them to summon their heroic virtues and fight.

There’s not nothing here. I wrote in my GODZILLA review that:

Here is a film that, had it been made in … oh, say, 1954 … would have been taken as an apologia for Japanese rearmament and a social reconciliation with war veterans (as well as the obvious A-bomb trauma theme). It’s made explicit in this film that Japan can’t count on the US to defend it and it now needs war veterans and their military expertise to fight Godzilla. Pacifism isn’t an option socially and the human story is a coward recovering his manhood by fighting (I saw this with my MMA coach and his girlfriend).

But some of Washburn’s claims about the film are dubious. It’s not really the case, either in history or in the film, that the Japanese soldiers and sailors “resent” their defeat. They’re definitely humiliated by it and lament the ruin and death all around them, but they don’t “resent” it in the prideful, revenge-seeking sense the Southerners of 1866 or the Iraqis of 2004 did. IRL, the emperor going along with the surrender and retaining authority quelled a Japanese KKK or Fedayeen. In GODZILLA MINUS ONE, the subject just never comes up. The Americans are mentioned only to note their absence and there’s no blaming them for Godzilla, the latter despite the obvious fact that Godzilla was (and always has been in the movies) the product of the A-bomb attacks.

In Japan’s post-WW2 self-mythology, those attacks are an unthinkable metaphysical evil, the equivalent of the Holocaust to us, not something subject to debate (which they are here, and even opponents of them know this). If GODZILLA MINUS ONE were about vanquishing “Japan’s wartime enemies,” you’d expect at least SOME more anti-Americanism than “they won’t help us against Godzilla because they don’t want to upset the Soviets,” starting with something like “the American A-bombs created this beast.”

Indeed, the way I would put it is that GODZILLA MINUS ONE is about reclaiming the heroic virtues, at a very difficult time, in the name of better fights and of fighting better. On the former, these veterans are plainly using their skills to save Japan, not to rape Nanking. On the latter, there are lines about how careless the Empire had been with their lives, putting them in thinly armored tanks and in planes without ejector seats (all this is historically true), and this becomes a major plot point. And also … sets up the final denouement.

But those claims are just a bit misguided. Washburn’s true bizarrerie is the last 70% of the column. Of the piece’s about 1550 words, the 1100 beginning with “By a strange quirk of fate” are not about GODZILLA MINUS ONE or Godzilla movies at all but an essay about a book on Japan’s World War II atrocities. This is literally 2/3 of the piece:

[The Japanese were awful.]

[Rinse and repeat and repeat and repeat…]If a movie came out presenting recently demobilized Wehrmacht soldiers as heroes — and conveying the message that these Nazis may have taken a licking but still had some fight in them — audiences and critics around the world would rightly revile the film as the morally repulsive garbage it would be. Yet, in the face of all that [Gary J.] Bass documents in painstaking detail, Godzilla Minus One has grown into one of the most popular, lucrative, and, one might even say, beloved movies of the decade.

Something’s wrong here.

Yes, something IS wrong here, and it’s this kind of bedwetting-progressive pseudo-pacifism appearing in an American conservative journal.

Joking Twitter bio aside, I have absolutely no problem with noting that the Japanese fought in World War II like uncivilized barbarians indifferent even to their own survival. Or with cinematic depictions thereof, whether by whites (BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI) or by Asians (DEVILS ON THE DOORSTEP). I haven’t read the Bass book that fascinates Washburn, but whatever might be said of its systematicness and/or any specific new details, it really is no revelation during my lifetime that the Japanese fought like uncivilized barbarians. (I have a very vague memory of an extended family member whose name I can’t even recall now, having been broken by Japanese abuse after he was captured in Hong Kong or Singapore.)

But that doesn’t lead to two further propositions: (1) that the Japanese themselves must view their history as the work of uncivilized barbarians; and (2) that every representation of post-war Japan must center on being / having been uncivilized barbarians.

The first is simply a matter of national survival and national pride, two conservative virtues the rejection of which are central to the current Great Awokening. To put it simply and crudely, self-hatred is not a viable national self-image. It’s 1946 Japan … what are you supposed to do, going forward? And “going forward” means “don’t bomb Pearl Harbor” isn’t an answer. You have hundreds of thousands of blood-soaked soldiers and a whole populace that went along with every manner of atrocity.

Short of replacing the population (though keep in mind that this has been the norm of conquest for much of human history), you have to work with the “material” you have. Your only logical alternatives to national self-hate are to invent self-serving evasions — East Germany claimed it was the repository for all progressive elements in German history; Austria retreated into victimology and a kulturcentrism in which Beethoven was an Austrian and Hitler a German. Or you can start at “Year Zero” like the Khmer Rouge. These courses are not recommended, the last “most” of all.

Every self-respecting country needs a usable national story, even about “last week.” By this, I’m not talking about lying about history, and the verb I chose in point (2) was deliberate — “center.” What is the most-important thing, the alpha and omega? The 1619 Project is not awful because, in one of the anodyne euphemisms often used, it “teaches about slavery,” something to which no sane person objects. It is awful because its aim is “to reframe the country’s history, understanding 1619 as our true founding, and placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.” But a nation cannot respect itself, and will quickly collapse in self-hatred, if [Something Evil] is at its center. This would be an utterly uncontroversial point if applied to an individual. You can’t, for long, think you’re nothing but a sinner. Washburn is peddling the kind of anti-heroic nonsense once expects in Vox, but not in National Review.

Insisting that Japan’s uncivilized barbarism of 1945 is relevant in the face of an objective threat in 1946 (like say a fire-breathing, radiation-spewing giant dinosaur) is the kind of weird moral purism that masks the moral disarmament and practical delegitimization that one expects from the Wokest of the Woke. They are the ones who insist that some Israeli misbehavior(s) is the cause of Hamas’s October 7 massacre. I even remember way back a discussion board in which a leftist, on the night of September 11, fretted about being worried that he had heard somebody reacting to Bush’s speech that evening by yelling in a bar “get them towelheads” (or “Ayrabs” or somesuch). If only the sinless have a right to fight or use and nurture the martial and heroic virtues, then nobody does. Indeed, maybe this IS the hidden point of the bad-faith pacifist— again, a tactic I’d expect from many venues, but not conservatism’s historic flagship journal.

And to grab Washburn’s analogy by the horns, there’d be nothing in principle wrong with a movie about demobilized Wehrmacht soldiers as heroes and having the fight in them needed to preserve (West) Germany. As long as they’re not goose-stepping or Jew-gassing, what would the objection be? Only the mere fact they had been Nazis a few years ago, a group that’d be mighty hard to avoid in 1946 West Germany (or frankly East Germany or Austria either, but that’s another story). Unless a literal ethnic cleansing and population replacement is the remedy, you can only start from where you are and who you were yesterday. If a monster comes to destroy your capital, the fact you were uncivilized barbarians last year only means you shouldn’t fight the monster to those who are Peak Woke. Or in National Review apparently.

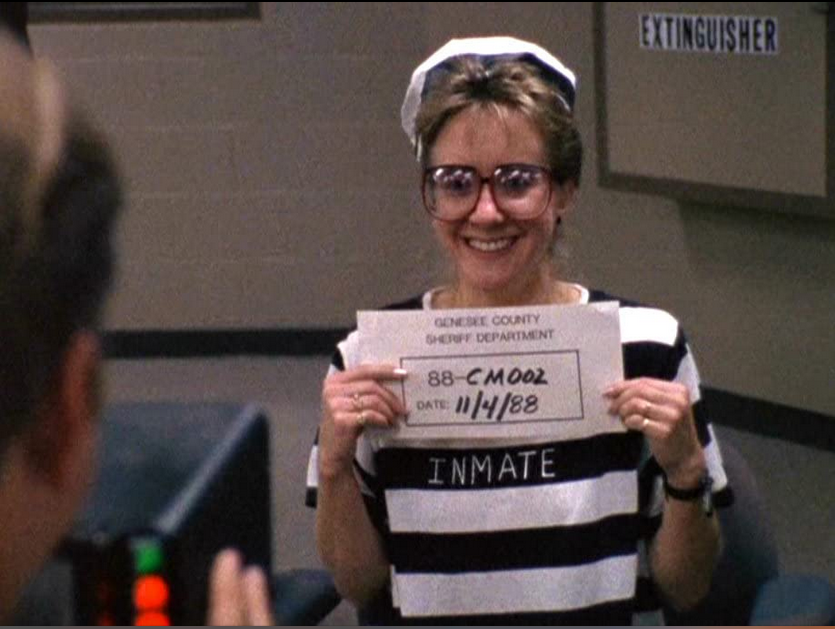

Unseen 80s project 2 — When Harry Met Sally

WHEN HARRY MET SALLY (Rob Reiner, USA, 1989, 5)

It’s the most famous scene in the movie, indeed one of the most famous in any 80s movie … and it exactly exemplifies why WHEN HARRY MET SALLY left me cold. I simply and flatly don’t believe for one second that any woman would fake an orgasm in a crowded deli … or any public place. Especially not for the sake of a debater’s point with a man she only intermittently knows. Noway. Nohow. Not unless she were Emma Stone in POOR THINGS where there are … extenuating circumstances. But a woman tolerably raised in any conceivable society, much less an upper-middle-class late-20th century American woman? Nope.

Nor is this isolated … I never bought anything in WHEN HARRY MET SALLY, which is one long writer’s device masquerading as a movie. Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan are obviously both hugely appealing, but they are playing two of the most written characters I’ve ever seen. They don’t talk like people but like the Chat GPT for Romcom Epigrams (forgive the anachronism … and its cuteness; but if you love this movie, you’d better accept that much). Only their inherent charisma, plus Crystal’s relaxed comic flair (Ryan is trying too hard), keep the movie watchable rather than collapsing from all the preciousness.

Also let me make two comparisons with films that I love — Woody Allen and Richard Linklater’s BEFORE movies. Indeed between the plain white-on-black credits and the opening use of a pre-rock standard (they continue throughout) WHEN HARRY MET SALLY comes on like an Allen movie, especially once it settles into its Manhattan milieu. Woody’s dialogue is also epigrammatic by any standard, but his plots and characters often manage to surprise us and he varies tones within his films; Reiner is producing a straight formula that hadn’t changed since the 30s plus a fake orgasm. The endings of MANHATTAN and ANNIE HALL (or if you want a less-Olympian standard the “life goes on” in VICKI CHRISTINA BARCELONA) put this happy-end contrivance to shame. Speaking of “shame,” the BEFORE movies actually manage to convincingly portray a couple falling in and out of love amid coincidences and chance over the years, but is so much more minutely crafted and developed in its trajectory that … I wanted to be watching of those movies.

I know that people treasure WHEN HARRY MET SALLY. And it IS very quotable and the characters have a lot of tiks that you could discuss and talk through — Ryan’s Karenesque restaurant ordering; Crystal’s phone messages; and the debates about CASABLANCA and opposite-sex friendship. OK OK … this is a romantic fantasy not a neorealist movie. I get that. And I can hear y’all saying “Victor, you sourpuss. It’s a movie romcom, not a slice of life — but a piece of cake, in Hitchcock’s formulation.”

But like with LOVE ACTUALLY (another treacly holiday confection that makes me sound curmudgeonly) there is a formal device that gives the lie to that excuse. After each break in the contemporary action, Reiner cut to a real-life aging couple giving a documentary style interview about how they met or got together. It’s a Woody-like device and at the end Reiner shows an interview with Crystal and Ryan. Exactly like the “love actually is all around us at Heathrow” montages and collages at the beginning and end of LOVE ACTUALLY, this device tells us that what we just saw IS real life. Er … no. Now TBF to WHEN HARRY MET SALLY, it doesn’t approach the level of toxicity that LOVE ACTUALLY does, if for no better reason than that there is only one inevitable and overdetermined happy ending versus 3627282 inevitable and overdetermined happy endings (number approx). And it is often superficially entertaining; just not a classic.

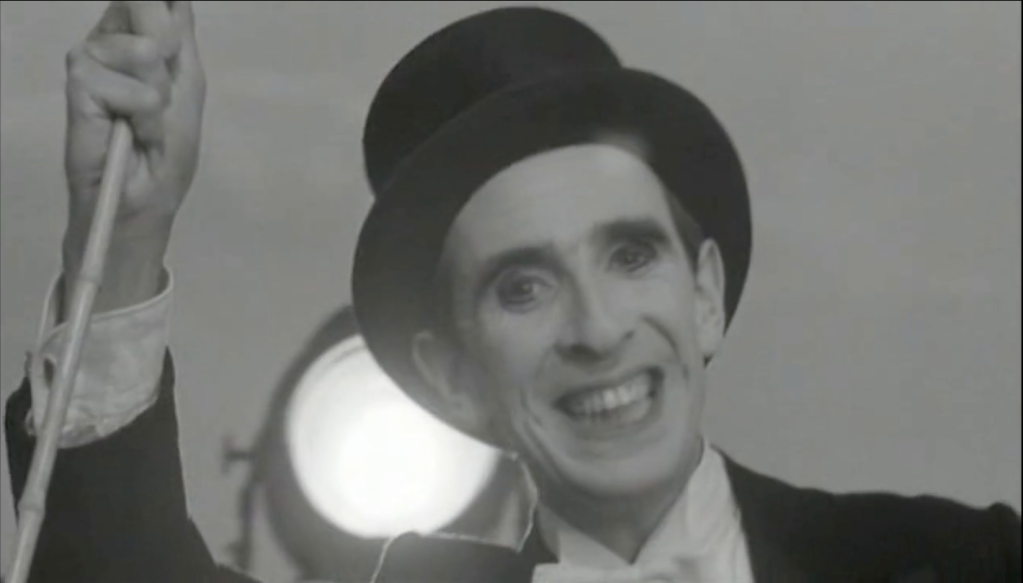

Films of My Life – 4

The first 3/4 of this was written years ago for a series called “Films of My Life” about the movies that shaped my critical and cinephilic mind, which is not at all the same thing as my all-time favorite films. I had the first five titles mapped out, published two (on THE BREAKFAST CLUB and AMADEUS) and largely written the next two, DR. STRANGELOVE, published last week, and this one on Federico Fellini’s 8 1/2.

8 1/2’s claim to “fame” (in the context of this series anyway) is not only that it was among the three foreign films that I first rented and the only one that I really liked, i.e., the first foreign film I liked. But more than that, it’s been a life lesson at several times over the decades through more than a dozen viewings. It’s officially my fourth-favorite film of all time.

In 1988, I had just gotten the film-viewing bug and begun to camp out at video stores. At the time though, like most Americans at that age I suspect, I had never seen a foreign-language film but I knew that was one of the prerequisites to a proper film education was cosmopolitanism. So at the recommendation Roger Ebert’s Home Movie Guide, I went to an H-E-B Video Superstore and rented three Fellini films — LA DOLCE VITA, AMARCORD and 8 1/2. I watched LA DOLCE VITA first with my father but honestly was quite bored by it (so was my father) because I just wasn’t mature enough, in the sense of my viewing habits, to attune myself to it yet. I remember my dad said something like “it’s about whether Marcello Mastroianni is really happy.” A couple nights later, after having fidgeted my way through AMARCORD alone in my room, he and I watched 8 1/2 together.

At the end, he said “what was that all about?” I replied with a big, stupid grin on my face “I’m not sure, but I loved every minute of it.” I learned later that 8 1/2 can profitably be compared to James Joyce (whom Fellini insisted he’d never read), but on this day I had learned the first key lesson of watching foreign films — that a snooty art movie can still be fun and engaging and witty, even in the absence of the simple three-act structure on which we all cut our teeth as children (and which many never grow out of). And a movie can thrill you in ways you might not be able to explain immediately.

What I loved about 8 1/2 seems obvious to me today — the character of Guido, a director and an obvious Fellini stand-in I could tell even then, as a confused man trying to maintain an appearance to the world; the look of the film and how the black-and-white images of what looked to be actually just black things and white things; the faces and the way they not-really-break the fourth wall by “regarding” the camera rather than addressing us a la Brecht; and the obvious and undeniable virtuosity in every element of the cinematic art — the music, the sound mix, the editing, the way people seem to float rather than walk.

But most of all I dug Fellini’s sense of humor, something that was, to my young eyes on those days, absent from LA DOLCE VITA and AMARCORD (don’t worry buds … I obviously did come around on those two films later). What I think I found most attractive was its self-deprecating quality. When the critic tells Guido that his film is “a series of complete senseless episodes,” and “doesn’t have the advantage of the avant-garde films, although it has all of the drawbacks” I laughed precisely because, on the surface, he’s describing 8 1/2. The episodic and meandering non-plotty quality that (I later decided) made LA DOLCE VITA and AMARCORD hard for me was no longer alien or off-putting to me. Fellini was doing the film equivalent of “why I don’t want to write this essay,” something I actually did as a high-schooler at an open-ended “describe yourself” essay. His sensibility and authorial persona was just attractive to me in a way that to this day I’d only apply more to Alfred Hitchcock. My favorite Roger Ebert excerpt on Fellini came later, from his Great Movies column on AMARCORD:

Fellini was more in love with breasts than Russ Meyer, more wracked with guilt than Ingmar Bergman, more of a flamboyant showman than Busby Berkeley. He danced so instinctively to his inner rhythms that he didn’t even realize he was a stylistic original; did he ever devote a moment’s organized thought to the style that became known as “Felliniesque,” or was he simply following the melody that always played when he was working?

But when I read Ebert on Fellini at the time, the line that stuck with me was from a review of AMARCORD: “Someone once remarked that Fellini’s movies are filled with symbols, but they’re all obvious symbols … [LA DOLCE VITA’s Christ statue] … AMARCORD is obvious in that way with a showman flair for the right effect.” Fellini was a showman, which was the sugar that made it all go down so smoothly. 8 1/2 a movie that slips in and out of reality and fantasy and dreams and flashbacks but (and you’ll just have to trust me on this) I never had any doubt what I was watching. I knew the orgy was a fantasy, that the first view of Saraghina was a flashback, albeit probably a stylized one, that Claudia Cardinale was a real person initially being hallucinated but appearing at the end, and that the critic probably hadn’t been hanged.

You’re perfectly free to take this as a flaw in my sensibility, but 8 1/2 taught me at a very “young” age that complexity needn’t mean obscurity and thus that obscurity is not excused by a desire for complexity. 8 1/2 has nothing in common with MEMENTO except this, but both films tell impossible narratives while being as crystal-clear and well-signposted as a Dick and Jane. I also can’t deny the ego boost of watching a film that might come across as intimidating but being able to follow it, enjoy it and enjoy following it.

I later took an Italian Cinema class in which Professor Millicent Marcus showed two Fellini films (8 1/2 and GINGER AND FRED) and she said Fellini was the only Italian film-maker whom “everybody, even my grandparents in Kansas” know about. For my class paper on 8 1/2, I wrote a rebuttal to Pauline Kael’s negative review of that film, having been shocked that she couldn’t see its greatness. Along with Siskel and Ebert on TV (plus to a lesser extent Ebert as a writer) Kael was the greatest early influence on me as a critic. Her writings were what I aspired to … small-d democratic in tastes, journalistically specific in her descriptions, sure in her judgments, obvious in her sensibility and thus position, funny and personable in her writing. But … “wha’ happen?” I thought (forgive the anachronism). How did she not see what is great here? Here were some of the excerpts from that review that I rebutted.

“can one imagine that Dostoyevsky say or Goya or Berlioz or DW Griffith, or whoever resolved his personal life before producing a work, or that his personal problems of the moment were even necessarily relevant to the work at hand?”

“when a satire on big expensive movies is itself a big expensive movie how can we distinguish it from its target? When a man makes himself the butt of his own joke, we may feel too uncomfortable to laugh?”

“It’s more like the fantasy life of someone who wishes he were a movie director, someone who has soaked up those movie versions of an artist’s life…”

Analogy with too-big houses losing their personality “when the movie becomes a spectacle, we lose close involvement in the story … It has become too big and impressive to relate to lives and feelings.”

I looked for my paper to see if I could quote from it, but, while I know I didn’t throw it away, it must be packed away with the boxes I’ve put in storage. The points I remember making is that the 2 of those 4 artists I knew something about very well DID make work out of their personal problems and wrestling through their demons; that we shouldn’t distinguish a work from its target in a meta-film, otherwise it’d come across as hectoring; that homages from directors like Paul Mazursky and Bob Fosse to Woody Allen and Francois Truffaut seem to indicate it’s not a fantasy idea of a director; and that spectacles are involving too (see … er … D.W. Griffith).

I got an A (I got an A or A- on all 10 of the reaction papers we had to write and Ms. Marcus said before the first that she graded our reaction papers on a curve where only about 10% would be judged as A) and I remember she or the TA wrote “very entertaining and thorough … much of what Kael says is, as you say, inarguable taste, but you do extract out what in her analysis IS arguable.” But the important lesson I got from the paper was … even your idols can be wrong. Or as Kael Herself once wrote:

He is not necessarily a bad critic if he makes errors in judgment. (Infallible taste is inconceivable; what could it be measured against?)

I’d’ve always said about 8 1/2 that “it’s more profound than it seems and not in the ways Guido ‘tries’ to make a ‘profound’ film”… BUT… my most recent view of 8 1/2 came in 2021 one day after a deeply depressing MMA training session in which my coach said (more than once in varying formulations) “this isn’t the time for self-criticism.” But this showing on that day was serendipitous as Fellini’s happy ending became tearfully cathartic and wise, instead of seeming, as it sometimes does, a bit artificial and pat. Or as Kael famously said ”’accept me as I am’ is Guido’s final, and successful, plea to the wife figure (although that is what she has been rejecting for over two hours).”

My greatest roadblock as a fighter is that I’m extremely self-critical and have often thought of “tearing down the set” because of my fight-related failings. That critical quality is what made me an avocational film critic in the first instance, but one friend with whom I’ve shared shirtless physically pleasantries once said to me “don’t review yourself like you’re a movie.” The way the critic puts it in the second-last scene, as Guido’s set is being torn down, is that it is better to destroy than create if you’re not creating those few things that are truly necessary. If I’m not good enough, I should walk away. I can’t accept myself as I am. But no. The clown invites Guido to come out and walk away from the self-criticism. All the characters in the parade look at Guido lovingly. I’ve been told by professional MMA fighters and numerous others that I’m an inspiration to them and I don’t always believe them in their parade, seeing myself, in the critic’s phrase, as the cripple who leaves behind his crooked footprint. But what of this sudden joy that makes me tremble, gives me strength, life?

On that day, Fellini gave me a reason not to tear down the set.

Zac Efron. Wrestling picture. What do you need, a roadmap?

THE IRON CLAW (Sean Durkin, USA, 2023) 5

So the Von Erichs are another thing that Jimmy Carter effed up.

More seriously … the opening subjective shot is amazing. And my gut was personally kicked (and “stiff”) watching this after a training day so shitty I cut it short in despair. The physical plant, looks and in-ring action are great and indeed pro wrestling, because it’s staged, might be the ideal “sport” for the movies to portray. The relationships and rivalries among the brothers sometimes work; but the problems … WHOOOO! That WHOOOO! is actually the only complaint I’d make about the wrestling, other than that there’s not enough of it. The guy who plays Ric Flair isn’t convincing. It’s not just that the voice is wrong, but he just hasn’t got … it. That’d just be caviling if THE IRON CLAW as a whole were great, but as it is …

The basic problem with this movie is that it’s just a lot of events over decades, or “biopic shapelessness.” The title of the post is a Coen Brothers joke, but I wish it weren’t applicable. If you walk in knowing the basics of the Von Erichs’ history (and I did as I was a huge pro wrestling fan — a mark probably — at the time and saw them wrestle on TV many times), you don’t need a roadmap. But all the film gives you is one. Such thematics as there are (besides “bad … <yawn> … dad”) are also just plopped in in a moment. THE WRESTLER told a story; depicting IRL events is not telling a story. The ghost of Chris also haunts the film and I’m just not convinced that his death would have been too much tragedy as Durkin has said. There’s already A LOT of that and the absence of one becomes a greater presence when it’s “only” be a matter of five brothers dying rather than four.

Despite its 132-minute length (the film blessedly doesn’t feel that long), there’s still just too many events to cover. Whole threads get reduced to one scene or asides … Kerry jumping to WWF, Kerry’s painkillers, Kevin wanting to sell WCCW, mother’s religiosity. Mike’s in-ring career is unbelievably (in the bad sense) brief and teleological — we go from him never having entered the ring to in consecutive scenes having one hard day training to his career-ending, near-fatal shoulder injury.

There are also TWO unforgivably sentimental happy endings. The earlier one is exactly the sort of cloying scene that makes atheists think Christians are deluded sugarcoaters, while the latter happens merely because it happens. Kevin is left “standing strong” alone for no reason, except that the death parade ended IRL so the movie now must too. The roadmap is over.

No camp, just fun

GODZILLA MINUS ONE (Takashi Yamazaki, Japan, 2023) 8

Remember how TOP GUN: MAVERICK last year was “what if TOP GUN were good?”? And I joked below about AMERICAN FICTION as “what if BAMBOOZLED were a good and smart movie” Well, here is “what if GODZILLA were good?” It’s a pleasure to see a monster movie like this with first-rate production values, that takes itself seriously, has not a trace of camp or cheese value, and has a compelling human drama as its core (as well as a monster that is pure evil, not some misunderstood whatever).

I jokingly call myself in my Twitter bio as “Japan WW2 apologist.” Here is a film that, had it been made in … oh, say, 1954 … would have been taken as an apologia for Japanese rearmament and a social reconciliation with war veterans (as well as the obvious A-bomb trauma theme). It’s made explicit in this film that Japan can’t count on the US to defend it and it now needs war veterans and their military expertise to fight Godzilla. Pacifism isn’t an option socially and the human story is a coward recovering his manhood by fighting (I saw this with my MMA coach and his girlfriend).

I didn’t realize going in how much of a Godzilla fan Nicholas and Jessica were (I knew he was a genre film and anime fan). But both had seen numerous iterations of Godzilla. FWIW … they both thought it was amazing and he said he had a tear in his eye at the climax. It was Nicholas who told me afterward that this film is a return to the Toho original in portraying Godzilla as pure malevolence, while many of the subsequent films have at least somewhat “humanized” the character. He also told me that this is a return to having Godzilla move like a dinosaur (i.e., short, inflexible front limbs and stiff hips … occasioning a joke about my jujitsu) rather than almost human-like; which in the 1954 film was a result of the budget/technology necessity of being a human in a rubber suit. They were also both amazed when I told him the one thing I knew about the film going in (besides the generally positive buzz) … that it was made for $10 million. “Good gawd, what’s Hollywood doing with all its money” (or something close to that) was his reply.

Gonna see this one again before year-end voting

POOR THINGS (Yorgos Lanthimos, Britain, 2023) 8

Lanthimos is nothing like the Dardennes, except in one respect — his sensibility is extremely Victoresque. His demento sense of humor and his ideas of meaningful stylization are so like mine that he probably just needs to be himself and fully realize and finish his film (I haven’t been crazy about some of his non-endings) for me to love it.

There’s apparently some notion afoot here that Mark Ruffalo is giving a bad performance as Emma Stone’s beau in this film adapted from Glaswegian author Alasdair Gray (a formulation upon which fellow cinephile Chris Ward and I insist). He is ideal … even the “inconsistencies” — he’s an invader into the hermetically sealed world created around Stone, so he’s in it but not really.

Most of all, Lanthimos actually finishes this movie and takes its fairly obvious Frankenstein metaphor — the alien/robot/beast who becomes human — to its logical end, realization into humanity at … a cost. To some.

The writing here is just about perfect — the ill-fitting combination of Yoda-esque kid talk of unfiltered id and the baroque “overwritten” lines of 19th century literature, representing the two sides of the film.

And rare for a very “written” movie, which POOR THINGS obviously is, it’s stunning visually, though I wish Lanthimos had stayed with black-and-white interweavings to end of the film. But those overheated hypersaturated colors in Lisbon, on ship etc makes it all look like Fauvist painting. You won’t see a better looking ship or sea shot this year, next year, last year, etc. Like the dialogue, it’s brilliantly stylized in a relevant way. Indeed, I already thinking was thinking after I typed this up that I’d underestimated the movie.

Noticing things anew

RESERVOIR DOGS (Quentin Tarantino, USA, 1992) 9 R V

Technically I saw only 90% of it after channel-scanning. I used to think DOGS was crude in that “first” film way, probably because so much of it is essentially people talking on a “stage.” But post-HATEFUL EIGHT it’s now obvious that this is just QT’s preferred metier.

Three reactions I don’t recall having before in my fourth (I think) viewing:

(1) Tim Roth would have placed highest on my 1992 Skandies-if-they-existed ballot, as he has both the key role (the cop who can’t be the moral center because he’s a fink) and best scene (rehearsing and telling his back story — a visualized flashback that’s explicitly a lie). Presenting a falsehood as if it were real is exactly the sort of what-if exercise QT has since come to be known for — he’s basically made two whole films with that premise, but it’s the kind of thing that used to be considered a no-no — see how much excrement Hitchcock took for a misleading flashback scene in STAGE FRIGHT.

(2) I always thought part of QT genius in PULP FICTION was withholding the obvious tour de force scene, there it was Willis winning the fight he supposed to throw and even killing his opponent. That happens again here in that we don’t see the robbery but I don’t think any of his subsequent films messed with audience expectations in quite that way.

(3) DOGS is actually less confusing than I remember having thought. Or maybe the fact I knew I missed the first 12 minutes or so meant I subconsciously accepted that confusion. But at a minimum, I think every character acts in an intelligible way throughout until everything becomes obvious in the last scene.

Christmas leftovers

These are the films I saw in December on which I had a bit less to say on Twitter.

MONSTER (Hirokazu Kore-eda, Japan, 2023) 4

If there’s anything worse than a gimmicky narrative structure that doesn’t work, except as a trick and subterfuge, it’s a film that tells the same story that your favorite film of last year told straight, if subtly and allusively.

I’m not naming the film to avoid spoilers, which is exactly the problem … it’s not until iteration three of the same basic story events told from three perspectives (the mom, the teacher, the boy) that The Central Topic becomes apparent or even that strongly hinted at. I don’t hate the film like some do because Diversity, but it’s unfair to us regardless.

Though I have to be honest … the film really got off on the wrong foot with me in the scenes with the mom and the school officials, which simply pass the point of believable bureaucratic indifference. They aren’t acting like politely indifferent ass-coverers; they’re barely even acting like zombies.

Of course no thread about a Kore-eda movie will be complete without noting his penchant for MOR classical piano tinkling. Though in fairness, I should add the film’s most notable departure from that musical style and into the horn section may have been its best moment (until that got effed up too).

EILEEN (William Oldroyd, USA, 2023) 6

Know what was a fantasy … a Masshole bar drunk circa 1960 saying “a left hook like Joe Frazier” rather than Rocky Marciano. That was merely annoying as a boxing fan … but the film was near-great until The Twist.

What we had for so long was an overheated seduction movie with Anne Hathaway AnneHathawaying up the joint (Sirk in the midst of drab neorealism), and Thomasin McKenzie just barely registering her words in a muted sound mix.

As for The Twist … I’m fine in principle with it except for where the film goes with it specifically. It’s pure Therapeutic Society hokum about Bad Dads that then forgets Anne. A part of me was thinking the whole movie might be an OWL CREEK-type fantasy (we get lots of foreshadowing false scenes), but we’re clearly meant to see the end as final liberation, which … ick and ugh.

OUR TRIP TO AFRICA (Peter Kubelka, Austria, 1966) 2 s V

Remember in CRIMES AND MISDEMEANORS that documentary that Woody made about Alda? This film is like that film .., only it’s in real world and not in a comedic movie. Maybe if you consider hunting and white tourism to be a priori evil, you’d consider these Kuleshov juxtapositions, both visual and aural, to be somehow profound. I sure as heck wouldn’t know. Kubelka does let us see African boobs and dick though, which is not at all exploitative.

THE TEACHER’S LOUNGE (Ilker Catak, Germany, 2023) 6

If it had an ending, we’d add one or even maybe two to that.

Much of this film is a reductio ad absurdum of small-d democratic education and its melting before actual human behavior, including gossip and procedural authority … or perhaps LE CORBEAU transferred into a school setting. Leonie Benesch is excellent at the center, as the new teacher who tries to advocate for students, but only makes things worse for herself and everyone else. It’s familiar territory — Bildung as disillusionment — but never quite applied to this context.

But LOUNGE doesn’t want to go for the jugular a la APPROACHING THE ELEPHANT. It shows educational authoritarianism all right, at the start even, but it can’t bring itself to say education is authoritarian. So it paints itself into corner it can’t resolve on its own small-d terms. It just gives us a pointed non-ending.

THE BOY AND THE HERON (Hayao Miyazaki, Japan, 2023) 3

Another case where I’d advise the director’s fanboys to ignore me. I’ve never been much of a fan of world-building and even universe-building, and the deeper this one got into it, the less my interest became. Pretty much checked out mentally by the time the parakeets showed up, though there was a good movie in the “real” world about step-parents and some potentially fun comedy with the old servants.

But this film was critically clarifying for me about why world building so often leaves me cold. It requires exposition dumps about a world with which I’m necessarily unfamiliar, which is both boring and necessary to remember. If you’re not already carrying around the mythology in your head, it leads to events that make no sense, either as plot or as theme. You eventually get sunk in the quicksand trying to follow it even if the imagery is sometimes amazing. What the rules of block stacking, for example, have to do with mother loss is … unclear at best.

EMBRYO LARVA BUTTERFLY (Kyros Papavassiliou, Cyprus, 2023) 6

I saw this yet-undistributed film, about a scrambled timeline pregnancy, at the AFI Silver’s EU Film Series, and wrote up my reaction at Letterboxd.

OPPONENT (Milad Alami, Sweden, 2023) 7

I saw this yet-undistributed film, a Payman Maadi wrestling/refugee movie, at the AFI Silver’s EU Film Series, and wrote up my reaction at Letterboxd.

AMERICAN FICTION (Cord Jefferson, USA, 2023) 7

Or what if BAMBOOZLED were a good and smart movie (which is very definitely a fiction)…? Lee was held back by terrible-looking 2000 video, an awfully conceived Damon Wayans performance, and a really stupid and unbelievable premise (white people would watch blackface on anyone but a left-wing politician). This one is just much better calibrated and Jeffrey Wright isn’t a caricature.

The film is held back only by its own manifesto-worthy point that black life is more than the easy mass-commodified images, especially the caricatured ones highlighted here as more “authentic.” Which is undoubtedly true but, as Hitchcock said, drama is life with the dull bits cut out. Much of the domestic drama here is those dull bits and I wasn’t crazy about the early death.

So yeah, I wanted the movie the trailer was selling … all literary-scam material, more social satire about white consumption, “blackness,” fakery. The best scene is the one between Monk and fellow black author Sintara Golden about their two books, which … does not go the way I was expecting when it started.

SILENT NIGHT (John Woo, USA, 2023) 2

Maybe John Woo just isn’t my bag. I saw THE KILLER in 1989 or 90 and had not otherwise ever seen a Woo movie. obviously SILENT NIGHT wasn’t trying for my sweet spots (I largely shrugged at the hyperemotionalized “gun fu” of THE KILLER). But I do like SOME violent action films — ONG-BAK first comes to mind — and this one is just empty.

I like dialogue. It helps movies make sense. I like characterization. It gives movies stakes. I don’t inherently like violence. It hurts. I like some basis in reality. It also helps movies make sense. I like emotional restraint. Its lack is cheap.

I could buy that the lead character (Joel Kinnaman) doesn’t speak as a character feature. But to have nobody speak like a normal human being is just an affectation. The only scene I wasn’t bored by was the one-shot ascent up the stairs. The choreography and camera movement is the work of a virtuoso. All else was just stuff and dough.

A FISH CALLED WANDA (Charles Crichton, Britain, 1988) 10 R V

Seen for just the second time in a decade, but surely the 10th or 12th time overall, and it struck me more than ever how, once the basic situation with the jewels is set up, the film is completely fat-free and goes from memorable comic set piece to memorable comic set piece without the slightest concession to “normal” events.

You also have four great comic performances in completely different registers. Kline and Palin are both playing caricatures, but Kline with far more … zest (in the character anyway) while Palin is perpetually … held back (no, I don’t mind it one bit). The contrast between the two is why the goldfish scene between them is great. Curtis and Cleese are more believable human beings, but with a similar polarity — she’s a schemer and he’s a mark.

SALTBURN (Emerald Fennell, USA, 2023) 3

Imagine KIND HEARTS AND CORONETS, only rewritten by Tennessee Williams’ po-faced Chinese knockoff and directed by Lee Daniels’ non-union Mexican equivalent — though that probably makes this movie sound more awesome than it is.

I have a taste for the lurid but not if devoid of humor (unless you find the story so over the top it’s automatically funny … which … fine, I guess). But my tolerance for someone mourning by fucking the fresh grave dirt and ending with unsimulated nude dances is … limited. And yes, despite recent attempts at reclamation, the oversexed, ultra-stylized “thrillers” from the 80s and 90s WERE dumb as a bag of hammers.

Unseen 80s project 1 – BIG

BIG (Penny Marshall, USA, 1988) 8 V

Last year I began a project to catch up on 80s classics that I had never seen. Like with many things, I kept at it for a while and then just dissipated. But I did see about a half-dozen films, two of which I’d say are great — INDIANA JONES AND THE TEMPLE OF DOOM and VIDEODROME. And prompted by something I don’t wanna say, I decided to pick it up again. I had made a list of about 40 films, some of them “you haven’t seen THAT??” jaw droppers and I took a look last night at BIG, which had been sitting on my DVR since last year.

I of course remember BIG — it was a huge hit and made Tom Hanks a major star. Prior to this, he had starred in a sitcom and had made low-budget, low-prestige movie comedies. And I was “familiar“ with BIG’s most famous scene, simply from pop-culture osmosis — the FAO Schwarz piano scene. But what had osmosified its way into my brain was that Hanks did a solo dance on the piano playing “Chopsticks.” That was a mistake, Victor. I’ve now looked it up. And the other person was important in the film too; a wonderful Robert Loggia playing a crusty old executive without overdoing the crustiness.

The first thing that struck me from the movie proper though, because it’s the first thing we see, is how much technology has changed in 35 years. (I had some of that same reaction to some of the other films I caught up on.) We see the 12-year-old boy who’ll eventually become Tom Hanks play a computer game that might politely be called “early” and not much later he and his best friend are talking on a big pair of plastic walkie-talkies that might politely be called “an early smart phone.” There’s a later scene about another way that the world, or rather Hollywood and the media, has changed in 35 years. Let’s just say you would not see people speaking Spanish used this way in a 2024 remake.

Hanks ends that scene, taking place at a dump hotel that he’s rented because he knew no better, by closing his windows and blinds, wrapping his pillow over his head, and crying himself to sleep. Exactly like a 12-year-old boy. For this premise to work (boy wishes he were grown up, accidentally gets his wish because of some magic Maguffin) the adult actor has to convincingly be a child doing his best to be an adult, and never quite succeeding. (For those not alive at the time, there were about five or six age/body-swap movies released in the decade’s last couple of years and comparisons were inevitable.) There were big moments of Hanks acting like a child — the sundae, the spray can — but he also nailed the smaller details, like the restless way he skipped along a split-level pavement with one leg on the upper level and one on the lower level, and how he vigorously raised his hand at a corporate board meeting when the presenter (teacher) asked if there were any questions. The film also has a lot of fun with language misunderstandings such as whether he pledged in college and inviting a girl to sleep over.

That woman (a coworker played by Elizabeth Perkins) provides the countervailing conflict by falling for Hanks, while he’s sort of falling for her in his very inexperienced way. After initially wanting to go back to being 12, he starts enjoying being an adult especially if you have a job as vice president of product development at a toy company. And getting a princely salary. AND A GIRL?!?! I I was kind of hoping at first that the two would never kiss but then once they did (to Glenn Miller … which is now almost as close to BIG than BIG is to now), it was inevitable that their second sleepover wouldn’t be like their first.

But I found it intriguing, in both good and bad ways, how director Penny Marshall handled it. She showed nothing. Was she trying to avoid the obvious implication of technical sex with a minor by not showing sex with the body of the adult Tom Hanks? That seemed weird, but then what happened next was exactly right. Afterward, Hanks is acting like an adult in his gait, speech and gestures. (Well … as adult as he could, at this stage of his career — very far into the future was his blossoming into an eminent dramatic actor.) It was as if he had … ahem … been made a man. A quite profound reversal then happens … he sees kids acting like kids, and THIS makes him want to go back to being a tween. In the hands of a director and scorer not so insistent on sugaring up everything, it might’ve been gut wrenching — acknowledgment that man is doomed to unhappiness, always enviously wanting what he can’t have because he can’t have it. As it is, it’s just slightly bittersweet.

Still, Marshall’s direction of the last scene was lump-inducing in part because of technology. In the 2024 remake (that’s not an exhortation, Mr. Hollywood) we’d see Hanks walking away from the car and his body morphing a frame at a time back into that of David Moscow. Instead, because it was 1988, we get a cut to Perkins and then a cut back to a very ill-fitting pair of pants, another cut back to her, and then Moscow wearing a suit that David Byrne would’ve thought too big.

I do, however, have one major reservation about BIG. The similar-premised films of the time had a father-son or mother-daughter swap. Here, the boy just becomes an adult. That difference helps in some ways regarding dramatic focus but a true swap means that the parent is in on it and the question of parental knowledge never gets raised. In BIG, the writers handle that in the worst way imaginable, by having the parents (principally, the mother played by Mercedes Ruehl) believe their adult-bodied boy has just gone missing. Kidnapped, with police and milk cartons and everything. But the film largely ignores (and kinda must for tonal reasons) an investigation that lasts about two or three months. I could never get out of my head while watching Hanks in New York as a toy executive what was happening on the homefront. Hanks makes a phone call and then writes a letter home, playing along with the kidnap story, but we never see the reaction to the letter. And speaking of “never see” … the very last shot. It all just plays as cruel, especially in the movie that, while terrific overall, is otherwise a featherweight comic fantasy.

Siskel and Ebert sold out

It’s been common for some time to lament how film journalism takes trailers and other clip releases as actual news and/or the basis for critical discussion. It’s all a sop to marketing and the corporatization of the critical enterprise, etc.

Well TIL … Siskel and Ebert actually “reviewed” a trailer. For FULL METAL JACKET in 1987.

I saw that segment as part of an hour-plus video, one of many “Siskel and Ebert review Auteur X” labors of love, by YouTuber Vanilla Skynet. The whole video is worth watching, if a little disjointed. But scroll to the 35:30 mark to get to their segment on the trailer for FULL METAL JACKET, which they played in its entirety.

I had a couple of reactions to this, in addition to the “OMG, they were reviewing a trailer?” shock.

First is that I think some of the root of Ebert’s (to my mind inexplicable and wrongheaded) disappointment with the film can be seen here. Gene and Roger’s fights (plural) about FULL METAL JACKET are among the greatest segments in the show’s history and the main release-week review comes right after the segment on the trailer. But in that segment on the trailer, you see that Roger believes, not wrongly mind you, that Kubrick had made another Strangelovian satire. And the film, though great in my view, is not that. His written review even makes it explicit that Joker’s Ann-Margaret line Is just an isolated gesture, and that he was “waiting for Kubrick to spring a surprise, but he never does.” Roger got trailer-fooled.

Second, it reminded me of my own reaction to FULL METAL JACKET, which was extremely mixed at first. I saw it on cable TV, ca. 1989 and I so hated Lee Ermey’s character and so identified with Pvt. Pyle, the chubby physical fuckup (a sentiment to which I’m not immune today even as a fighter) that I found the movie uncomfortable and even a bit humiliating. If you’d ask me at any time during the first half of the film what I thought of it, I’d’ve said “I hate this” while really meaning “I hate him.” When Ermey gets killed to end part one, I don’t think I’ve ever been made happier by a death — real or fiction (yes, I’m including monsters like Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden). However, then the second half inevitably felt like an anti-climax. So for many years, I had a great deal of sympathy for Ebert’s view that the film was too top-heavy and “never recovers” once it leaves Parris Island. I suppose I still hold the view that the first half is better than the second half. But I now see that as testament to what great performances Ermey and D’Onofrio gave and I understand better what the film was going for in its second half — the consummation and ironic realization of the first half in making these men killers.

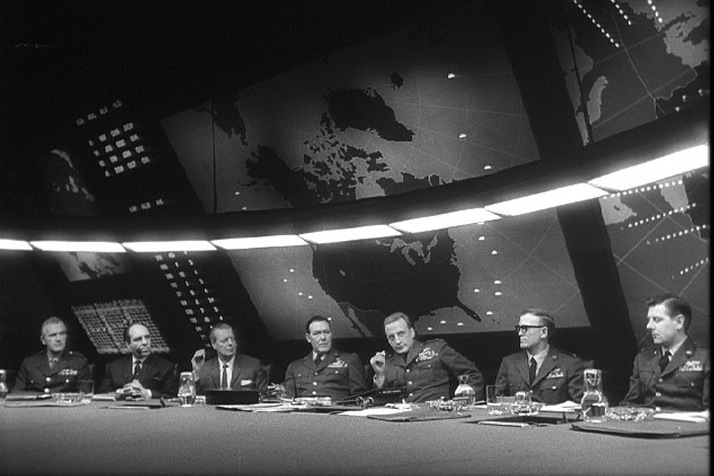

Films of My Life – 3

This was (mostly) written years ago for a series called “Films of My Life” about the movies that shaped my critical and cinephilic mind, which is not at all the same thing as my all-time favorite films. I had the first five titles mapped out, published two (on THE BREAKFAST CLUB and AMADEUS) and largely written the next two, this piece on DR. STRANGELOVE just needing some smoothing and polishing.

DR. STRANGELOVE is one of only three films in my Official All-Time Top 10, CASABLANCA and A CLOCKWORK ORANGE being the others, that I saw for the first time in my pre-cinephile life. As I’ve said, prior to about 1988-89, I rarely went to movies, and never went by myself. I saw maybe 3-4 films per year in theaters, always while going out with family members or friends. DR. STRANGELOVE was one such excursion – while I was in college and my life revolved around policy debate. Stanley Kubrick’s film (he was so well-known that even I at least recognized that name at the time) was playing at the campus film program and about 4-5 of us on the debate team went.

I can’t speak to now, but at the time, near the end of the Cold War we thought would never end, nuclear weapons and nuclear strategy were subjects that college and even the better high-school debaters knew backwards and forwards — the better to debate huge impact events, as anything in the world could be argued as leading to tyranny, nuclear war, all Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, etc.

I spent much of high school and a couple of college years immersing myself in material most teens don’t even know exists, much less would go near. I would devour every issue of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, the US Naval Institute Proceedings, Orbis, The Futurist, Foreign Affairs and others, read books by the likes of Herman Kahn, Richard Pipes, Angelo Codevilla, etc. and collect extremist rag sheets that made incredible but powerful-sounding claims (“the only viable alternative to an inevitable nuclear war is for the Russian and other captive peoples to rise up and overthrow the Soviets,” read claims by the ABN Correspondence, written by … ahem … Ukrainian Nazi-symps … ahem … who turned out to be correct). To this day, there are still a few cards I can recite off the top of my head in full “spread” delivery — Masotti, 69, on race riots leading to a fascist US that would start a nuclear war; Beilensohn and Cohen, 82, on US membership in NATO guaranteeing a nuclear war; Dean, 84, on a rebellion in East Germany leading to a panicky Soviet invasion of NATO; Sanguinetti, 84, on the LDCs never being able to repay their debts … ah … good times.

So I went in to DR. STRANGELOVE, at least at first, primarily out of interest in the subject matter and without realizing that it was a comedy. The film’s semi-documentary opening scene giving “the other side” from the US Air Force, and the early procedural scenes at Burpleson AFB and even Gen. Turgidson’s pad, promised something more serious. One thing that never ceases to amaze me upon more than 20 viewings of what has remained an all-time favorite and still my answer to the question, “what is the funniest movie you’ve ever seen” is how DR. STRANGELOVE eases into what eventually becomes wild caricature.

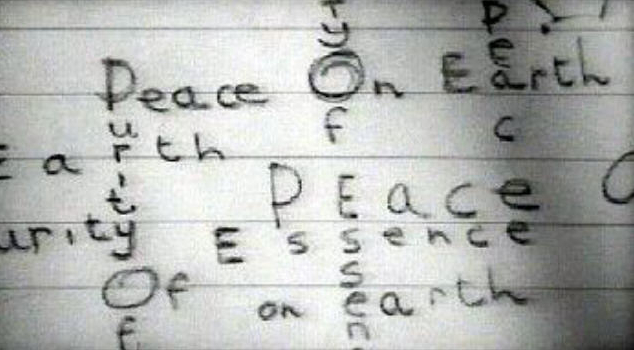

The “purity of essence” speech and the whole name Jack D. Ripper, for example, both come near the film’s midway point not at the start, as both “name” and “motive” should come according to the Sid Fieldses of the world. It’s also the emphasis Kubrick gives the names in the delivery. The Russian ambassador’s name is De Sadesky and the premier’s name is Kissoff (some people attacked the film at the time as being at the level of Mad magazine). But I missed both names the first few times I saw the film because they were tossed off, not delivered as punchlines. DR. STRANGELOVE is funniest when it’s not trying to be funny — if the film had been a uniformly frenetic farce, it would have been unbearable. Reason #5705761236501 Stanley Kubrick is a genius: Cutting out the custard-pie fight that was supposed to end the film.

That touches on the first thing about DR. STRANGELOVE that impressed a college-debate military-journal dork for whom “counterforce” and “countervalue” were as much a part of what he breathed (and argued over) as “less filling” and “tastes great” were for most of his peers. And who would have punished any break from realism most harshly. DR. STRANGELOVE was the first film I’d ever seen, and still pretty much the only one, that goes very deeply and interestingly into military strategy, but which I can’t see through. It provides a gripping story that makes good use of getting accurate every detail of the technology and the use-scenarios. Kahn, believed along with Henry Kissinger and Edward Teller to be one of the principal sources for the Strangelove caricature, discussed a device in the 1950s very much like the Doomsday Machine and concluded, in Dr. Strangelove’s words, “that it was not a credible deterrent for reasons which at the moment should be all too obvious.” But such a device was technically possible, Kahn discussed its pros and cons with a straight face, and he concluded that it would only even be theoretically credible if it were triggered automatically. And, in Kubrick’s movie, Dr. Strangelove explains, in excruciating detail that parallels Kahn’s, that the Doomsday Device has to be triggered automatically for the very reason that no sane man would ever trigger it.

But what I will never forget from that night was the moment when the Soviet ambassador describes the Doomsday Device to the US leaders in the War Room. I whispered to the debater sitting next to me: “why would you build a weapon like that and not do it publicly.” He responds to me “yeah, that doesn’t make sense.” Not 10 seconds later, Dr. Strangelove barks at the ambassador “Of course, the point is lost … IF YOU KEEP IT … A SECRET!! VIE DIDN’T YOU TELL US!!!! “

I knew DR. STRANGELOVE was a masterpiece at that point.

Some years later, I saw DR. STRANGELOVE again at a different campus screening, though this time I went in as a cinephile and someone who knew it was comedy, who knew and loved Stanley Kubrick, and who was certain that this was no peacenik movie (more on that anon). I was able to get, as was and is my general wont, an aisle seat. Sitting in the aisle seat in the row behind me was a girl whom I will never forget — Women’s Studies Major from Central Casting, looking like Cassandra on BEAVIS & BUTT-HEAD. As I was giggling at the climactic scene of Kong struggling to open the bomb hatch, she was giving audible upset gasps. When the bomb landed and the screen went white, the sounds began to resemble sobs (I obviously couldn’t see). I began laughing even harder. And then Kubrick vindicated my reaction with the last scene. We’re back at the Pentagon War Room, making survival plans that are obviously completely and totally unaffected by either personal interest or geopolitical gambits. “Mr. President, we must not allow … a mine-shaft gap!”

Although DR. STRANGELOVE has been read since 1964 as a “distrust warmongers/The Bomb” movie, I knew from then that it’s a lot more than that. And that’s the lesson the film imparted to me that has never left me as a conservative-laming film buff. Never trust political readings of movies as left-leaning. Often they will be correct, the inevitable result of the industry’s leanings and artists’ temperament. But if they’re right-leaning or left-critical, that fact will either (1) go unnoticed / be rationalized away, or (2) become the basis for attack, sometimes on pretextual “aesthetic” bases.

Topical satires of the moment are thin gruel and don’t last 60 years at least, as this film has, when compared to the grander points the film ultimately has on its mind – a Martian’s-eye yarn about the amusingly pathetic people on the planet next door and how they managed to destroy themselves one sunny day.

The coda gives the lie to topicality-mongering and reformism. What the mine shaft scene points out is how man doesn’t, perhaps cannot, learn. After all, what has just happened is the most salutary object lesson imaginable and yet, the men in the War Room STILL act as they did before. Further, STRANGELOVE does not willy-nilly take the view that political hatred blinds us to our common hum … zzzzz. At least one important fear of Turgidson (the immediate cause of the famous “you can’t fight in here; this is the war room!” line, in fact) is shown to be true – the ambassador WAS carrying a camera for spying. Further, the ambassador is quite clearly shown to be equally fascinated with Dr. Strangelove’s ideas for survival. As Stanley Kauffmann put it, the Doomsday Device in this movie is Man.

To satirize a particular action like “the Cold War ‘arms race’ ” requires a sense that things could be otherwise. To criticize “arms races” as such pretty much requires the corollary belief that political conflict is somehow illusory. If, on the film’s terms, a nuclear war and the deaths of billions of people wouldn’t change man, it’s hard to see what could. STRANGELOVE is Swiftian misanthropy, a joke on the human race told from the point of view of Olympus or Mars. From man’s view, the real political conflicts justify arms races; and for gods or aliens, man is a joke not worth worrying about.

The other universe-defining irony of the film is seeing individual sanity both producing and trying to deal with an inconceivably screwed-up situation — the disjunction of individual reason and cosmic reason. In fact, to put it bluntly, it’s only because the generals and presidents and bomber crew are NOT insane that the film is funny. And that was a realization that us debaters all had. In DR. STRANGELOVE, it’s man’s improvised wits and fortitude that both doom the world (the bomber crew) and save it (the coda).

The other track on which DR. STRANGELOVE is not a peacenik movie is that the “warmongering” isn’t (mostly) motivated by warmongering or bloodthirst. And to the extent that it’s motivated by sex — that’s kinda irreformable too. For one specific thing, the Doomsday Device is specifically situated by Ambassador de Sadesky as an alternative to massive military expenditures and a way to provide nylon stockings. This isn’t a joke line – in fact, it’s cognate to the very logic of the entire U.S. nuclear arsenal of the 1950s, which was overwhelmingly superior to that of the Soviets so the U.S. and NATO wouldn’t have to match the massive Red Army. The Doomsday Device is a Soviet mirror image of the same strategy — higher-level checkmate.

For another, Wing Attack Plan R is not a fantasy, but the only response possible to an actual strategic threat — a nuclear decapitation of the country’s leadership. That scenario had became more relevant as technology advanced in the Cold War’s subsequent decades to the point where I began studying nuclear weapons. Given that the principal delivery systems of the early 1960s were subsonic bombers, the lead times in STRANGELOVE were measured in hours with plenty of time for the drama to unfold. But in the 1980s, a depressed-trajectory submarine-launched ballistic missile from international waters off the mid-Atlantic could achieve that in a few minutes. And if something like Wing Attack Plan R didn’t exist somewhere in the Pentagon’s war plans (and the Kremlin’s), I’d’ve been very distressed.

And finally, as caricatured as the persons are, their responses to the film’s events are entirely rational and what I’d’ve expected. Without some nasty twists of fate that cannot be attributed to anything other than blind chance — Premier Kissoff’s love of surprises, the specific way the bomber was damaged, the bomber crew’s improvisations once their plane gets damaged — reason and military technology would have been the solution to its own dangers.

The film shows man and his ingenuity as both contemptible AND inspiring. Laugh at the mine-shaft survival plan generated by Strangelove’s foresight, but what else are they supposed to do now that the Doomsday machine has been triggered but to try to survive? Strangelove’s plans seem reasonable, and though there’s obviously that very dark undercurrent of “man doesn’t learn” from both Turgidson’s and DeSadesky’s behavior and though the satire continues (abandoning monogamy “will be a sacrifice we shall have to make”), is there any real doubt that this is what will happen and some remnant of mankind will survive? And their kids will look like Brendan Fraser.

The foreign-film Oscars

The Academy released today the 15 films short-listed for the best foreign-film Oscar and that picture is how the Wrap headlined its story. Europe bad! The second graf calls the list “very European-centric” though whether this not-quiiiiiite falling into the critical-theory rabbit hole is simply uncertainty about the official jargon (it’s “Eurocentric”) is unclear. But you’d call it “European” if you WEREN’T implying the critical-theory worldview.

But in defense of Eurocentrism …

Setting aside particular issues of worthiness or unworthiness or snubs of this film or that, why should it be surprising that the best films would be made in rich countries with the longest-developed film industries (which would definitely include Japan, India and a few other non-white countries, BTW). Unless we’re simply going to have a continental quota system, like FIFA does with World Cup qualifying, in a typical year, Europe and a few other first-world countries in East Asia and elsewhere will produce more good or great films than other continents. By all means, be open to smaller or poorer countries … but in competition the chips have to fall where they may. (Yes, I oppose “equity” per se.)

Here is the list itself, with the ones I have seen at festivals marked in bold:

Armenia, AMERIKATSI

Bhutan, THE MONK AND THE GUN

Britain, ZONE OF INTEREST

Denmark, THE PROMISED LAND

Finland, FALLEN LEAVES

France, THE TASTE OF THINGS

Germany, THE TEACHERS’ LOUNGE

Iceland, GODLAND

Italy, IO CAPITANO

Japan, PERFECT DAYS

Mexico, TOTEM

Morocco, THE MOTHER OF ALL LIES

Spain, SOCIETY OF THE SNOW

Tunisia, FOUR DAUGHTERS

Ukraine, 20 DAYS IN MARIUPOL

To the extent I can comment, this is a good list, with the lowest-ranked film of the seven I’ve seen (FALLEN LEAVES) still being a 5 and that’s my Kaurismaki tepidness talking. I said on Twitter that the Finn’s fans should ignore me; this is very Aki. Of the other six that I like, there’s two I absolutely love — Tran Anh Hung’s TASTE OF THINGS and Jonathan Glazer’s ZONE OF INTEREST. If handled well and especially if it wins the Oscar, the French film could become a huge hit, albeit for shallow reasons — it can be consumed as “food porn” but the movie is so much more and better than that.

But in defense of nationalism …

I was stunned to see that Britain submitted ZONE OF INTEREST, though not that it was successful once it did/could. The major countries of the Anglosphere have been nominated before in the foreign-film category with films made in languages other than English but indigenous to the country — French for Canada, Welsh for Britain, etc. But ZONE OF INTEREST, about the family life of the commandant of Auschwitz, was set in Poland and spoken entirely (best I can recall) in German. The names on the credits, from my recollection, were mostly Polish. So when I tweeted about ZONE, I identified it as “Germany/Poland.” Other than writer-director Jonathan Glazer, which admittedly is a pretty big deal, and some financial hand in the multinational production, there is nothing British about ZONE. To the extent Britain can claim ZONE merely based on Glazer and money, why couldn’t Germany (also!) have submitted PERFECT DAYS or even THE TASTE OF THINGS been claimed by Vietnam. Language and indigenousness matter. Nobody would watch ZONE OF INTEREST and call it a British film, so I’m not $ure in what $en$e it$ hypothetical victory could be called a Briti$h win.

Jonathan Majors abandoned

Actor Jonathan Majors of CREED 3 and THE LAST BLACK MAN IN SAN FRANCISCO was convicted today of assault on his girlfriend, though he also was acquitted of the worst of the charges. Sentencing is set for February, at which he could get up to a year in prison, though non-jailing sentences are possible and probably likelier given his lack of a record.

But this is the part that caught my eye for this site:

Marvel Studios and the Walt Disney Co. dropped him hours after the verdict.

…

Marvel and Disney immediately dropped the “Creed III” star from all upcoming projects following the conviction, said a person close to the studio who spoke on condition of anonymity because he wasn’t authorized to speak publicly on the matter.

Before his arrest, Majors had been on track to become a central figure throughout the Marvel Cinematic Universe, playing the antagonist role of Kang. Majors had already appeared in “Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania” and the first two seasons of “Loki.” He was to star in “Avengers: The Kang Dynasty,” dated for release in May 2026.

Now this isn’t “cancel culture” in the morally-relevant and now-prevalent sense. Criminal convictions for assault are a serious thing and if he’s in jail, he obviously can’t be shooting movies.

But it IS a kissing cousin to cancel culture … the eagerness to preemptively cut professional ties with people for things not directly related to their job, as if employment were a moral union or part of a social-credit system, rather than “wage slavery” as old-school Marxists used to call it.

It is presumptive at best, totalitarian at worst, to assume that private employers (or colleges or other social institutions) are in the business of punishing criminal behavior. That’s what police, courts and jails are for. It’s why they’re collectively called “the criminal justice system” and not “movie studios.” What should have happened here is for Disney and Marvel to have waited for the sentencing, see whether that materially affected Majors’ availability, and then make other plans for those films if it did.

One thing liberals used to believe (and still do when it comes to voting [Democrat]) was that criminal convictions shouldn’t affect your employability and that once you paid your debt to society, the matter was over. When Robert Mitchum was sentenced to jail for drug use, he served 50 days (the rest of the 1-year sentence was suspended pending probation and good behavior), and then he walked right back onto the RKO lot, continued to make movies and was as popular as ever.

That’s what should’ve happened here.

Please just disappear

THE DISAPPEARANCE OF SHERE HITE (Nicole Newnham, USA, 2023) 3

I hadn’t given a thought to Shere Hite in probably 30-odd years when I saw the title of this documentary, but I immediately remembered “oh, her!” Based on what I remembered of her public career, I thought THE DISAPPEARANCE OF SHERE HITE had the potential to be interesting if it concentrated on the title or it could be a straight-up feminist hagiography that will have me arguing at the screen for two hours.

THE DISAPPEARANCE OF SHERE HITE is the latter.

My first moment of eye-rolling came when Hite (whose writings are voiced on the soundtrack by Dakota Johnson) says she took modeling jobs when in graduate school because all means of support, including any jobs and marriage per se “are prostitution with the system.” That’s the kind of radical-chic metaphor that collapses in a moment’s thought. Both Hite and HITE also have the annoying habit, endemic in the artistic uniparty, of attributing disagreement to “fear” or to, in the current cant, ideas being “weaponized” by The Bad People. For one thing, this is per se anti-intellectual only one step above “fuck off, asshole.” But for another, “fear” is good. It is the proper response to nutty ideas married to power such as … [looks at notes] “a new kind of physical relationship to go along with a more humane society” or sexuality “without labels, without repression.” Well, who could feat THAT? Both Hite and HITE have the annoying tic of entitled radicals to make the most provocative statements and then find it inexplicable (or worse, pathological) that others react as if they have been provoked.

What put me in rebellion against this film was its gendering of general taboos and mores. Yes, at the time Hite wrote her first report on female sexuality, people didn’t say “vagina” or “clitoris” in public spaces. But this wasn’t about “suppression of women,” as the film claims — you couldn’t say “penis” or “testicles” either. And the film doesn’t reflect on what it means apropos this and its related claim that feminist knowledge is constantly suppressed and forced to be relearned when, in a late scene, we see Hite appear on Stephen Colbert’s show and the language used there. One can say these taboos were stupid or that they repressed sexuality. Not women.

But what I mostly see in such self-satisfied left-wing issue films is the moments when the film forgets what it said or showed five minutes earlier, tripping over itself intellectually or inviting “what about” reactions. Two moments finally tore it for me.

(1) A talking head says the backlash against Hite came because in her third major book, about women and love, she claimed that 70% of married women cheated on their husbands, which caused numerous pollsters to try to replicate the finding and never getting close to that. The talking head said that Hite had had a similar share of married men cheating on their wives in her previous book “and no one was shocked by that.” Er … did she watch the earlier parts of the movie? Hite’s book on men yielded footage of TV stars like Gil Gerrard and David Hasselhoff, of whose discomfort the film makes great sport, and an all-male audience on Oprah roundly denouncing the book, admittedly on many additional bases.