The best film of 1935

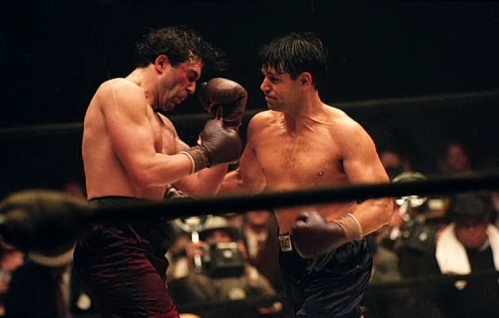

CINDERELLA MAN (Ron Howard, USA, 2005) — 8 (later upgraded to 9 on repeat viewings)

“Continued dependence upon relief induces a spiritual and moral disintegration fundamentally destructive to the national fiber. To dole out relief in this way is to administer a narcotic, a subtle destroyer of the human spirit.”

— Franklin Roosevelt.

Part of what makes the Depression-set film “Cinderella Man” such a surprising movie is exactly what makes the Roosevelt quote shocking. It’s a boxing movie, and I mean this in the best possible way, that could have been made in 1935. You can almost see Irish dynamo Jimmy Cagney in the role of underdog heavyweight champion James J. Braddock, played here by Russell Crowe in (yawn) another brilliant performance.

It’s not just the style (more on that anon), but the film’s values that tag it as maybe the Best Film of 1935. “Cinderella Man” is among other things a hagiography of a man from before the therapeutic society. Braddock’s entire being was wrapped in providing for his family and in honorable ways that did not include the disgrace of the welfare narcotic. In an early scene, Braddock’s son steals a salami, and he makes the boy return it to the butcher. And of course we get the famous tale of Braddock going on poor relief, shot from the other side of the office counter with his face criss-crossed by wire, like an inmate looking out from inside prison bars.

It’s not just the style (more on that anon), but the film’s values that tag it as maybe the Best Film of 1935. “Cinderella Man” is among other things a hagiography of a man from before the therapeutic society. Braddock’s entire being was wrapped in providing for his family and in honorable ways that did not include the disgrace of the welfare narcotic. In an early scene, Braddock’s son steals a salami, and he makes the boy return it to the butcher. And of course we get the famous tale of Braddock going on poor relief, shot from the other side of the office counter with his face criss-crossed by wire, like an inmate looking out from inside prison bars.

The film’s only real dalliance into politics is in the character of a radical friend of Braddock’s, played by Paddy Considine, who sneers at FDR and Hoover (“there’s no difference”) when Braddock expresses faith that Roosevelt has got some ideas to get things moving again, reminding us as only A Film from 1935 can, that there once was a time when the more left-wing of the two U.S. parties could call welfare a destructive narcotic and that, as newly-confirmed Judge Janice Rogers Brown put it, her “grandparents’ generation thought being on the government dole was disgraceful, a blight on the family’s honor.”

Is it time now to just flat-out say that Russell Crowe is the greatest actor-star of our generation? With a string of roles from “Gladiator” and “A Beautiful Mind” to “Master and Commander” and now “Cinderella Man,” has successfully filled the souls and bodies of four very different styles of patriarchs, from different eras and classes, but with the common thread of an unfeminized and unfeminist portrayal of masculine virtue. As a man, Crowe is neither an idealized god (like Clooney or Cruise) nor a self-consciously average-looking actor (like Norton or Dustin Hoffman). Boxing movies are unforgiving of an actor’s physique and physical comportment, and Crowe succeeds in *looking* like a 30s fighter, moving like a Depression icon, and fighting in a pre-Ali/Sugar Ray style.

Most importantly for a period piece, Crowe doesn’t have a post-modern bone in his body — none of his period heroes have a trace of the irony that is “the shackles of youth.” There’s no substitute for grown-up conviction, and Crowe has it. Little touches shows Crowe has gotten inside this man Braddock — e.g., before the Baer fight, he kisses his younger son and shakes hands with his elder son. Exactly — just as “Master and Commander” was filled with such touches. He’s a lapsed Catholic (“I’m out of prayers,” he says at one point), but genially so — he’s respectful toward the priest and acknowledges the devotion of his wife (Renee Zellweger, not really pushed in this kind of role) and children.

Most importantly for a period piece, Crowe doesn’t have a post-modern bone in his body — none of his period heroes have a trace of the irony that is “the shackles of youth.” There’s no substitute for grown-up conviction, and Crowe has it. Little touches shows Crowe has gotten inside this man Braddock — e.g., before the Baer fight, he kisses his younger son and shakes hands with his elder son. Exactly — just as “Master and Commander” was filled with such touches. He’s a lapsed Catholic (“I’m out of prayers,” he says at one point), but genially so — he’s respectful toward the priest and acknowledges the devotion of his wife (Renee Zellweger, not really pushed in this kind of role) and children.

The boxing scenes are simply the best of their kind I’ve ever seen. A couple of minor details that I, as a huge boxing fan, really appreciated. First, there is real boxing strategy and round-to-round trajectory in the fights, and as played by Paul Giamatti (in a performance in such a different key from his great performance in last year’s “Sideways” that it complements Crowe’s by its chameleonic quality) cornerman/manager Joe Gould gives Braddock sound advice between rounds that Crowe actually does follow through on. And in the later fights, Crowe-as-Braddock actually has learned to use his left better.

The comparably-good fight scenes in “Raging Bull” and “Ali” were in a completely different style and point — impressionistic shards of a sinner’s soul and the moments out-of-time that create a legend, respectively. Here, although there’s certainly subjective flashes to identify us with Braddock (a searing white light of pain when he breaks his hand, the scene going in and out of focus as Braddock’s head clears from taking a big punch e.g.), they’re more narratively compelling. They carry the drama throughout the film. We get cutaway shots to the crowd — standard boxing fare, except that the crowds vary, both in their size and in their reaction to Braddock, as he goes from promising contender to washed-up has-been fighting before a few hundred (“you’re a bum” the sound mix emphasizes at one point) to surprise victor and finally popular underdog champion with tens of thousands cheering for him. But Howard doesn’t know when to stop pouring on the audience-reaction cues with, for example, the flash images during the Baer fight of Braddock’s kids. Written in my viewing notes is “YES, I GOT IT, OPIE!!”

That gets to the film’s principal weakness. It’s by a director who can never leave his schmaltz well enough alone (a not-uncommon flaw for A Film From 1935). The portrayal of Max Baer, from whom Braddock takes the title in the climactic fight, is the clearest example of Howard not trusting the audience to “get” something until he’s underlined, circled it, italicized-and-boldfaced it, and highlighted it in yellow. Twice. There’s a scene where he taunts Mrs. Braddock at a nightclub, where a meeting between the two imminent opponents was “set up” with press present. Like the best trash talk, it seems to just go over the line into animus (think Ali-Frazier). Baer talks about killing or crippling her husband and how she’ll need “a real man” after that. And Renee tosses champagne on him in disgust. Standard promotion stuff, and I was expecting Baer to give Braddock the sort of “it’s all for the box office, kid” wink and a nod. But no. We’re supposed to take seriously that Baer was a boor?

And that score. Gawd. It actually diminished the climactic Baer fight for me (though that may also be a reflection of how much I admired the other fight scenes). But the mickey-mousing of cheap emotional cues, with reactions from the on-screen audience stand-ins helpfully provided (just in case), is slathered all over the scene like cheap gravy on a fine steak.

Still, it wasn’t ever thus. In one early scene, Braddock gives his daughter the last piece of meat, saying (falsely) that he isn’t hungry and he commits this simple act of paternal self-sacrifice without the Hallelujah Chorus on the soundtrack. In another, Braddock walks in on all the “suits” at an exclusive club who made their money promoting his fights. He begs for help, passing his cap around, saying he needs money to get his utilities reconnected. And Howard lets Crowe act the scene, carrying it with his well-shamed cheer, conveying his masculine pride both crushed and intact. The scene is near-silent, even dialogue-wise, and the camera doesn’t hold too much on the faces, manfully averting its eyes from the essential but unspeakable. And the scene is really affecting as a result. But the words “too much” seemed to have faded from Howard’s vocabulary as the running time progressed.

Still, it wasn’t ever thus. In one early scene, Braddock gives his daughter the last piece of meat, saying (falsely) that he isn’t hungry and he commits this simple act of paternal self-sacrifice without the Hallelujah Chorus on the soundtrack. In another, Braddock walks in on all the “suits” at an exclusive club who made their money promoting his fights. He begs for help, passing his cap around, saying he needs money to get his utilities reconnected. And Howard lets Crowe act the scene, carrying it with his well-shamed cheer, conveying his masculine pride both crushed and intact. The scene is near-silent, even dialogue-wise, and the camera doesn’t hold too much on the faces, manfully averting its eyes from the essential but unspeakable. And the scene is really affecting as a result. But the words “too much” seemed to have faded from Howard’s vocabulary as the running time progressed.